Insights - November 15, 2022

Cutting down Methane - our last best chance to keep 1.5°C within reach

Written by Rémy Kalter 5 min read

The most recent IPCC reports tell us that we have three years to peak global emissions and start to rapidly bring them down. The 2022 UN Emissions Gap report paints a stark picture indicating that we are really in the last chance saloon, with current policies setting us on course for 2.8°C of warming – a figure which should get more attention than it does as it more accuretly represents the steps actually taken to reduce our environmental footprint.

Little about how we have approached the climate issue to date would lead one to believe that we are able to shift our economic and political systems quickly enough to reach these targets - and that’s despite the technologies that would get us much of the way there already existing.

But there does seem to be some hope that we are getting our house in order. The European Commission has sent strong signals to the market through the European Green Deal and associated legislation. The passage of the first climate bill in the United States suggests the winds of change may be upon us.

There’s a good chance that this is all coming a bit too late. But we may have one final get out of jail card – if we tackle the issue of methane emissions. a subject of much focus this past year.

Methane - you may know it as the primary component of natural gas - a cleaner fossil fuel than coal or petroleum, the use of which many consider critical to a successful energy transition. Basically, you get more bang (energy) for your buck from an emissions perspective.

That it has become such a cause célébre is testament to the predicament in which we find ourselves.

Whilst it is a far more potent greenhouse gas than CO2, even though it doesn’t hang around for too long in the atmosphere - 12 years as opposed to several hundred for CO2 – by limiting how much we emit we can slow the rate at which we expend our carbon budget. Remember that methane is responsible for around 30% of the rise in global temperatures since the Industrial Revolution.

Basically, methane sets the pace for warming in the near term, and if we can get it under control, it buys us more time to get everything else right.

And the good news is twofold. Firstly, reducing a significant portion of our methane emissions is not all that hard nor is it very costly. And second, there is a precedent for such committed and short-term environmental action - the Montreal Protocol of 1987 that tackled ozone depletion and that prevented between 0.5°C and 1°C of global warming. To date, it remains the only multilateral environmental agreement ratified by all UN member states and is a landmark example of successful collaboration between public, private, technology and NGOs.

Getting methane emissions under control

Enter the Global Methane Pledge - a multi-government effort announced in November 2021 to massively cut back on the amount of methane being spewed into the atmosphere by 2030.

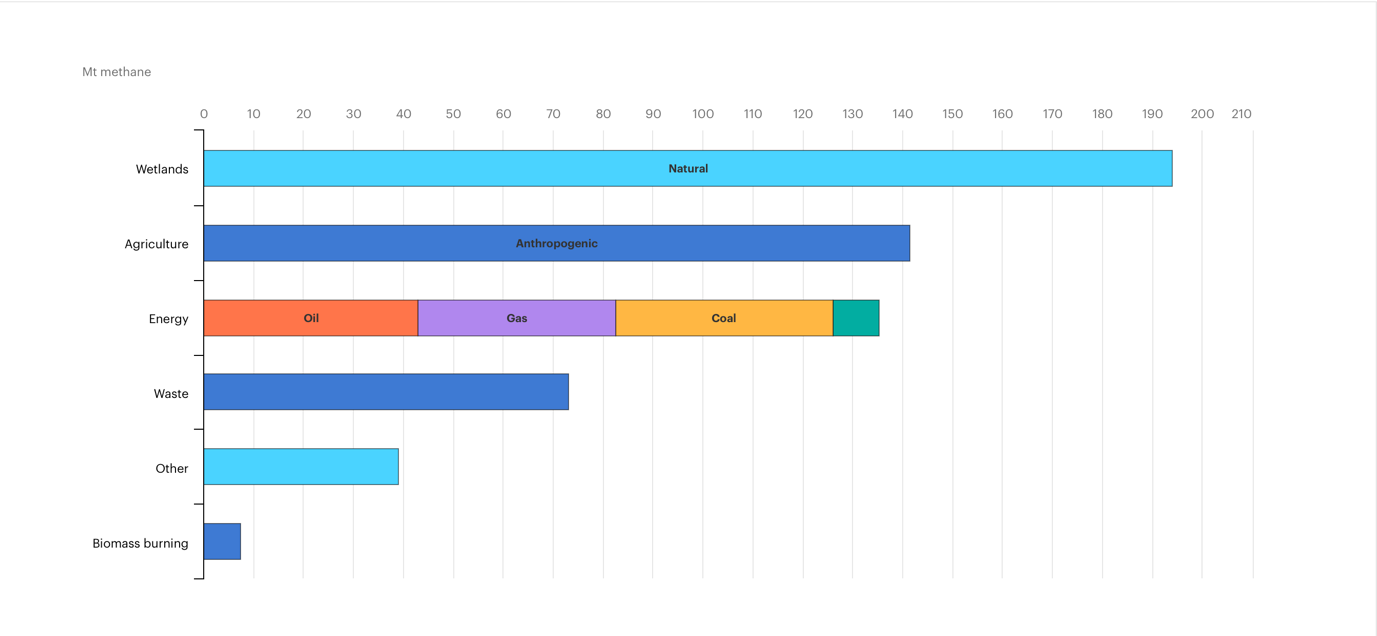

While reducing emissions from wetlands - the single largest contributor - by restoring their natural hydrological pattern may be attractive and is technically feasible, it can be extraordinarily complex “as many wetlands were drained for a very specific societal need (e.g., housing development, flood mitigation, agriculture), which may not be easily reversed.”[1]

[2] Aside from that, anthropogenic - that is, man-made - methane emissions account for 60% of the total, with agriculture the prime culprit followed closely by the energy sector (coal, oil, natural gas and bioenergy). Tackling these areas is quite a bit easier, and the solutions exist to make it happen.

Agriculture is of course a huge contributor. An effective way of reducing those emissions would be by impacting the diet and living conditions of livestock. This allows us to limit emissions from this activity by actually preventing the creation of those emissions in the first place, it being primarily generated by the waste and belching of this livestock.

Treating emissions emanating from landfills can also be effective, but even better if they are treated – and valorised – before they even get there. Solutions exist to transform waste into fuel, adding in an element of circularity. Capturing emissions from waste already in landfills presents a more practical challenge as the landfill is open and the emissions can emanate from every part of it.

That leaves the energy sector, which is probably where most effort should be focused. Within oil and gas, a significant amount of methane emissions come from a small fraction of highly emitting wells, referred to as super-emitters. A major challenge in reducing methane from oil and gas is to locate the super emitters, through new technologies such as methane sensors mounted to airplanes and satellites that are starting to be used for this purpose. Indeed, with “the next generation of satellites, we should be able to get to a next tier down of smaller and more distributed sources such as livestock operations, smaller landfills and specific oil and gas sites.”[3]

It may be even more relevant than initially thought to deal with the oil and gas sector first as recent research appearing in Nature concluded “that the aggregate level of methane emissions from fossil fuel production and consumption in recent years has been closer to 175 Mt/year rather than 120 Mt/year (which is about 45% more than was previously thought).”[4]

In addition, IEA analysis shows clear potential to reduce these emissions cost-effectively. Annual investment of around USD 13 billion would be required to mobilise all methane abatement measures in the oil and gas subsector. This is less than the total value of the captured methane that could be sold (based on average natural gas prices from 2017 to 2021), meaning that related methane emissions could be reduced by almost 75% at an overall savings to the global oil and gas industry.[5]

And there is a further incentive to do this; the United States government recently passed the Inflation Reduction Act which includes a provision whereby certain petroleum and natural gas facilities would be subject to a rapidly increasing “methane emissions charge” that would start at $900/ton as of 2024. Coupled with this are less punitive measures such as government grants to for methane monitoring and mitigation (currently present in the Canadian province of Alberta and coming soon to the US through the IRA, and price premiums for gas certified by third parties as having been produced with lower methane intensities.

Thus an urgent environmental need has been backed up with political backing and a financial penalty for inaction – a combination that is all too rare and shows the seriousness with which methane is being treated.

Furthermore, because evidence exists that historical emissions have been undercounted, measures used to measure and reduce these emissions must be reliable and accurate so that it can be clear how much oil and gas operators should be expected to pay for their emissions.

Coupled with the urgency of action is the need to make sure clear standards are adhered to throughout so as to build trust, especially as time is of the essence and there no space for backsliding. Fortunately, the technologies now exist that allow operators to pinpoint specifically where methane is being emitted.

Clearly there is great urgency to take action in this sector. It is critical that governments work to ensure all operators are treated the same way and adhere to common standards, as the speed at which action must be taken means there may be difficulties in getting operators to behave correctly.

Critically, technologies already exist to identify these leaks and begin treating them such as upstream leak Detection and Repair (LDAR), or Vapour Recovery Units designed to capture emissions that build up in pieces of equipment across the oil and natural gas supply chains.[6]

A political calculation

The economic case for capturing methane is that you can then combust it, producing energy and transforming harmful methane into less harmful CO2.[7] Rather than a hindrance, We may actually need to rely on methane capture and productivity to achieve our ambitions.

In an ideal world, where we could ignore economic and energy realities, one would capture methane and store it somewhere it can’t escape or do further harm. We don’t live in that world.

As the rise in overall energy demand continues to outstrip the rate at which we produce renewable energy, we continue to add capacity from traditional, fossil energy sources to keep up. As such our overall emissions continue to grow.[8]

Methane could be a valuable bridge to the energy transition as it buys us time to create enough renewable energy insfrastructure. The logic here is that capturing methane will not displace uptake of renewables but will displace investing in further exploration of more traditional fossil fuels - and this appears to be the calculation that has been made by most major polities, and particularly the European Commission, that includes natural gas facilities within its green taxonomy, thus making it eligible for sustainable financing.

It’s quite controversial to focus such effort on helping the oil and gas industry to clean up its act. Indirectly, one is contributing to the continued exploitation of these fossil fuels. It is also clear that if we are to have any chance of remaining on course to achieve our environmental targets, reducing methane emissions from the energy sector should be our priority, at least in the short term. It buys us time and may serve as a litmus test for concerted climate action in the 21st century, a model for the future reduction in emissions that is so critical over the coming three decades.

[1] https://eos.org/editors-vox/managing-wetlands-to-improve-carbon-sequestration

[2] IEA, Sources of methane emissions, 2021, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/sources-of-methane-emissions-2021, IEA. License: CC BY 4.0

[3] https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2022/02/03/cracking-down-methane-ultra-emitters-is-quick-way-combat-climate-change-researchers-find/

[4] We have probably severely underestimated these figures, and just this year global methane emissions from the energy sector are about 70% greater than the amount national governments have officially reported. A recent paper published in Nature examined historical ice cores and found that prior to 1950, natural geological sources of methane were much smaller (around 1-2 Mt/year) than has been generally assumed (between 40-60 Mt/year). As a result, the paper concluded that the aggregate level of methane emissions from fossil fuel production and consumption in recent years has been closer to 175 Mt/year rather than 120 Mt/year (as in IEA estimates).

[5] https://www.iea.org/reports/methane-emissions-from-oil-and-gas-operations

[6] https://www.iea.org/reports/methane-tracker-2020/methane-abatement-options

[7] To be clear, it is not orders of magnitude better - burning natural gas, for instance, produces nearly half as much carbon dioxide per unit of energy compared with coal - but it gets you heading in the right direction. But be careful; if enough methane leaks during production, its slim advantage over other fuels could be wiped out, hence the importance of monitoring and capturing effectively.

[8] https://www.cnbc.com/2021/11/04/gap-between-renewable-energy-and-power-demand-oil-gas-coal.html

Written by Rémy Kalter on November 15, 2022